Gravel spewed in every direction as the truck careened the corner from smooth pavement to dirt road. A quarter mile away, the sound of screeching tires and lumber thudding against the truck bed caused more than gravel to fly in the wee hours of the morning; seven children flew from their beds. Faces pinched and every muscle taut, their bodies flooded with stress-induced cortisol. Trembling, eyes dilated with dread, they awaited the truck’s headlights to illuminate the two massive pine trees standing sentry to the drive. Hope faded to despair once again as the headlights continued their sweep up the drive instead of the oft prayed for clash of metal against wood.

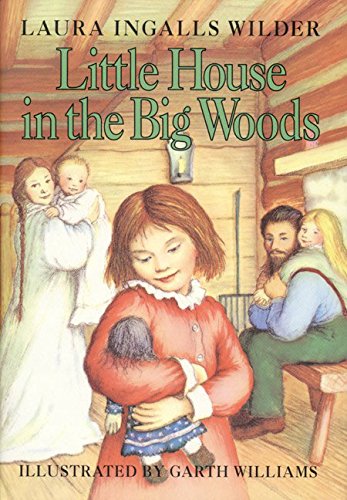

The next day, a child laid her weary head gratefully on her arms crisscrossed over her desk. Mrs. Luoma had picked up Little House in the Big Woods! Slowly, the nightmare images of a drunk father and all the ugly, terrifying reflections implied began to ebb with every soothing word the wonderful fifth grade teacher read.

Laura Ingalls Wilder did more than paint pictures with words for her blind sister, Mary; she painted a world of comfort where parents eased distress for their children instead of creating it, where families worked together to overcome struggles instead making them, and where families who loved could lift themselves out of despair instead of pummeling them down into it.

Each word caused the little girl to dream deeper and gather strength: maybe she could be a teacher, maybe she could have a life free of drunkenness, maybe she could break the cycle. Eventually, each dream did become a reality.

Fifty years later, I am still grateful for the alternative realism Mrs. Wilder supplied to my own constricted world and, even now, open one of her books whenever the world feels overwhelming.